Across the world, the end of life is marked in countless ways—some solemn, some joyous, and many deeply symbolic. Each culture carries its own traditions, shaped by history, faith, and values, to honour those who have passed and support the living left behind. While many Australians are familiar with traditional funerals, there has been a growing openness to exploring more personal and culturally diverse ways of celebrating life – this includes the rise of environmentally conscious services such as a green funeral in Melbourne, which provide families with a meaningful and sustainable alternative to conventional practices.

By examining how different cultures celebrate a life well lived, we not only deepen our understanding of humanity but also expand the possibilities of how we might like our own lives to be honoured.

Western Traditions: Reflection and Commemoration

In much of Western culture, funerals are typically solemn occasions, often rooted in Christian traditions. The service usually includes hymns, prayers, eulogies, and moments of silence for reflection. While historically these gatherings were more formal, there has been a notable shift towards personalised services in recent decades.

Families now often choose to celebrate individuality—by including favourite music, displaying cherished possessions, or crafting a service that reflects hobbies, passions, and achievements. The focus is no longer solely on mourning but also on celebrating a unique story.

The concept of a “celebration of life” has become increasingly popular, where guests are encouraged to share fond memories, laughter, and gratitude for having known the person. This evolution reflects a wider cultural move towards positivity, healing, and honouring a life well lived in a way that uplifts rather than solely grieves.

Māori Traditions in New Zealand

In Māori culture, tangihanga (funeral rites) are considered one of the most important ceremonies. These gatherings often last several days, during which the deceased lies in state at a marae (meeting grounds). Family and community members travel, sometimes from great distances, to pay their respects.

The tangi is not a quiet event—it is filled with speeches, songs (waiata), laments, and storytelling. It provides an open space for people to express grief, but also to celebrate the life, lineage, and cultural identity of the deceased.

Food is shared generously, symbolising unity and collective support. The tangi highlights the Māori belief that death is not the end, but part of a continuum connecting ancestors, the living, and future generations.

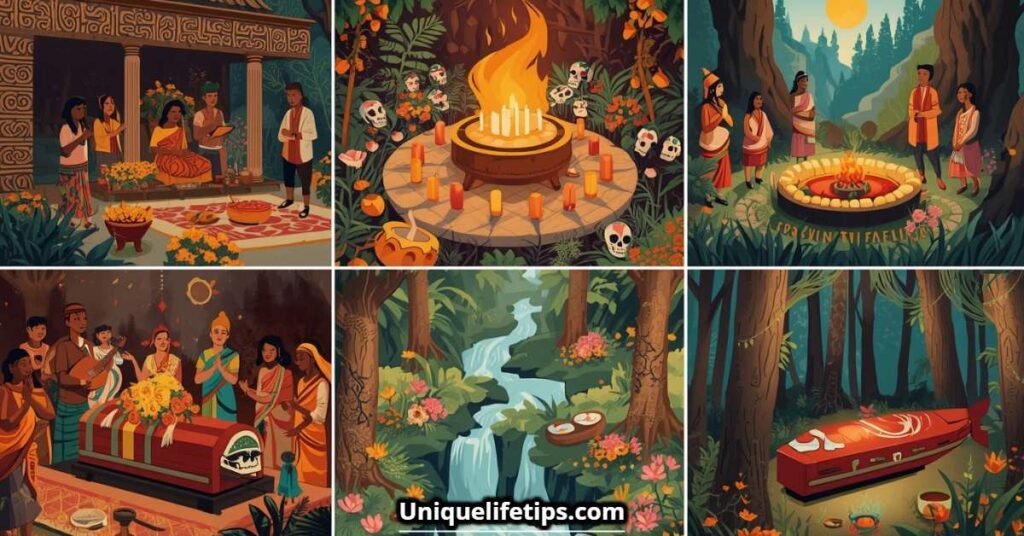

Mexican Traditions: Día de los Muertos

Few cultural celebrations of life are as vibrant and recognisable as Mexico’s Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Far from being a sombre occasion, this festival—held annually on 1–2 November—brims with colour, joy, and symbolism.

Families create altars (ofrendas) in their homes, decorated with flowers, candles, food, photos, and items loved by the deceased. Cemeteries become lively gathering places where families picnic, play music, and share stories by candlelight.

Marigolds, known as the “flower of the dead,” are believed to guide spirits back to the world of the living. Sugar skulls and traditional foods like pan de muerto (bread of the dead) are shared as part of the festivities.

Rather than focusing on loss, Día de los Muertos embraces the idea that loved ones remain spiritually present and should be honoured with joy, humour, and remembrance.

Hindu Traditions in India

In Hinduism, funerals are guided by the belief in samsara—the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The rituals aim to support the soul’s journey towards moksha, or liberation from the cycle.

Cremation is the most common practice, seen as a way of releasing the soul from the body. The ceremony often involves prayers, chants, and offerings to sacred fire, carried out by close family members. Ashes may be scattered in a holy river, most notably the Ganges, which is believed to purify and bless the soul.

Mourning periods vary by region and family tradition but often include rituals on the 10th and 13th days after death. These ceremonies are intended to help both the soul and the grieving family find peace.

In many Hindu communities, emphasis is placed on living a righteous life, so that death becomes not an end but a passage to the next stage of spiritual existence.

Buddhist Traditions Across Asia

Buddhism, practised across many Asian countries, views death as a transition rather than a finality. The rituals are designed to support the deceased in their rebirth and to remind the living of impermanence.

Ceremonies often include chanting by monks, offerings of incense and food, and the reading of sacred texts. In Tibetan Buddhism, the Bardo Thodol (often translated as The Tibetan Book of the Dead) is read to guide the consciousness of the deceased through the intermediate state between death and rebirth.

In countries like Japan, families may maintain a household altar where offerings are made regularly, ensuring ongoing remembrance and spiritual connection with ancestors. These practices highlight the Buddhist focus on mindfulness, compassion, and continuity, reminding loved ones that life and death are interconnected parts of a greater whole.

African Traditions: Communal Honour and Ancestral Bonds

Across Africa, funeral traditions vary greatly between regions and tribes, but they share a strong emphasis on community and ancestral respect.

In Ghana, for example, funerals are often elaborate, multi-day affairs featuring music, dancing, and strikingly crafted “fantasy coffins” shaped like animals, tools, or objects representing the life of the deceased. A fisherman might be buried in a coffin shaped like a fish, while a pilot could have one shaped like an aeroplane.

These celebrations reflect not only grief but also a recognition of the deceased’s role in society and the enduring connection to ancestors. Funerals are both a farewell and a reaffirmation of cultural identity.

The Rise of Personal and Green Funerals

While traditions differ across the globe, a unifying theme is the desire to celebrate life in a way that reflects values, beliefs, and connections. In Australia, this is increasingly seen in the growth of personalised and environmentally conscious funerals.

Families are seeking alternatives that feel more authentic and sustainable. A green funeral can include biodegradable coffins, natural burial sites, or services designed to minimise environmental impact. These practices not only honour the person but also reflect their values, particularly if they held a strong connection to nature.

This shift mirrors a broader global trend: the desire to make end-of-life rituals more meaningful, personal, and considerate of future generations.

What We Can Learn from Global Traditions

- Community support matters: From Māori tangihanga to African funerals, the gathering of community plays a central role in healing.

- Celebration can coexist with grief: Traditions like Día de los Muertos remind us that joy and remembrance can stand alongside mourning.

- Spiritual continuity provides comfort: Hindu, Buddhist, and many Indigenous practices emphasise the ongoing journey of the soul, offering hope to the living.

- Personalisation strengthens meaning: Whether through a fisherman’s coffin in Ghana or a playlist at a modern Australian funeral, individuality can shape rituals that truly reflect a life.

Final Thoughts

Death is one of life’s universal experiences, yet the ways we honour it are as diverse as the cultures of the world. Whether marked by solemn prayer, vibrant music, or environmentally conscious choices, each tradition offers wisdom about how to remember, heal, and continue the cycle of life.

As Australians become more open to embracing cultural diversity and new practices, families today have more freedom than ever to choose farewells that feel authentic, sustainable, and deeply personal. In the end, to celebrate a life well lived is to honour the stories, values, and connections that made that life unique—and to carry those memories forward with love.